Crowdsourcing Urban Accessibility Information for the Neurodiverse City Project

Written by Lucy Jiang

How can we leverage technology to make public spaces more accessible and inclusive?

New York City is home to over 2,000 public parks, nearly 600 privately owned public spaces, and countless other public areas. While these spaces are open to the public, they are only truly accessible when they can be meaningfully used by everyone — including neurodivergent individuals. Neurodivergence refers to a range of learning, cognitive, and psychosocial disabilities, such as ADHD, autism, anxiety, depression, and PTSD. Neurodivergent people often face barriers to fully accessing these public spaces due to built environments’ failures to consider their cognitive, sensory, and social needs.

Source: Design Trust for Public Space

In 2023, the Design Trust for Public Space launched the Neurodiverse City, a project that seeks to (1) learn from the experience and insights of neurodivergent community members, (2) collaborate with architects and design professionals to test potential improvements at two public sites in New York City — 200 Water Street and PS112, and (3) develop a scalable solution to empower neurodivergent people to navigate public spaces in the city and beyond.

As a Siegel Family Endowment PiTech PhD Impact Fellow in the summer of 2024, my goal was to propose a digital tool for collecting feedback and evaluating public space accessibility with and for the neurodivergent community.

Conversations with Design Partners and Advocates

Public spaces currently fail to consider the unique experiences, perceptions, and challenges faced by neurodivergent people. To build my understanding, I first met with two of my host organization’s design partners, uncovering insights from two workshops and sensory audits conducted in October 2023. The audits illuminated the diverse ways in which neurodivergent people prefer to communicate. For example, feedback mechanisms such as visual communication boards were found to significantly enhance inclusion for neurodivergent people who are less verbal or nonverbal. By offering multiple ways to collect information, we can respect neurodivergent people’s varied communication styles and foster richer engagement. These insights were critical in informing the design of my digital feedback tool.

Through our discussions, I identified four dimensions for designing a digital feedback tool:

Synchronous vs. asynchronous (i.e., whether the tool required a response in real-time while at the public space),

Guided vs. unguided (i.e., whether the tool involved a researcher to guide discussion and ask follow-up questions),

Text-based vs. multimodal (i.e., whether the tool could also take images or videos as input), and

Group vs. individual (i.e., assessing the space in groups or independently).

“...making public spaces accessible goes beyond making the place itself accessible.”

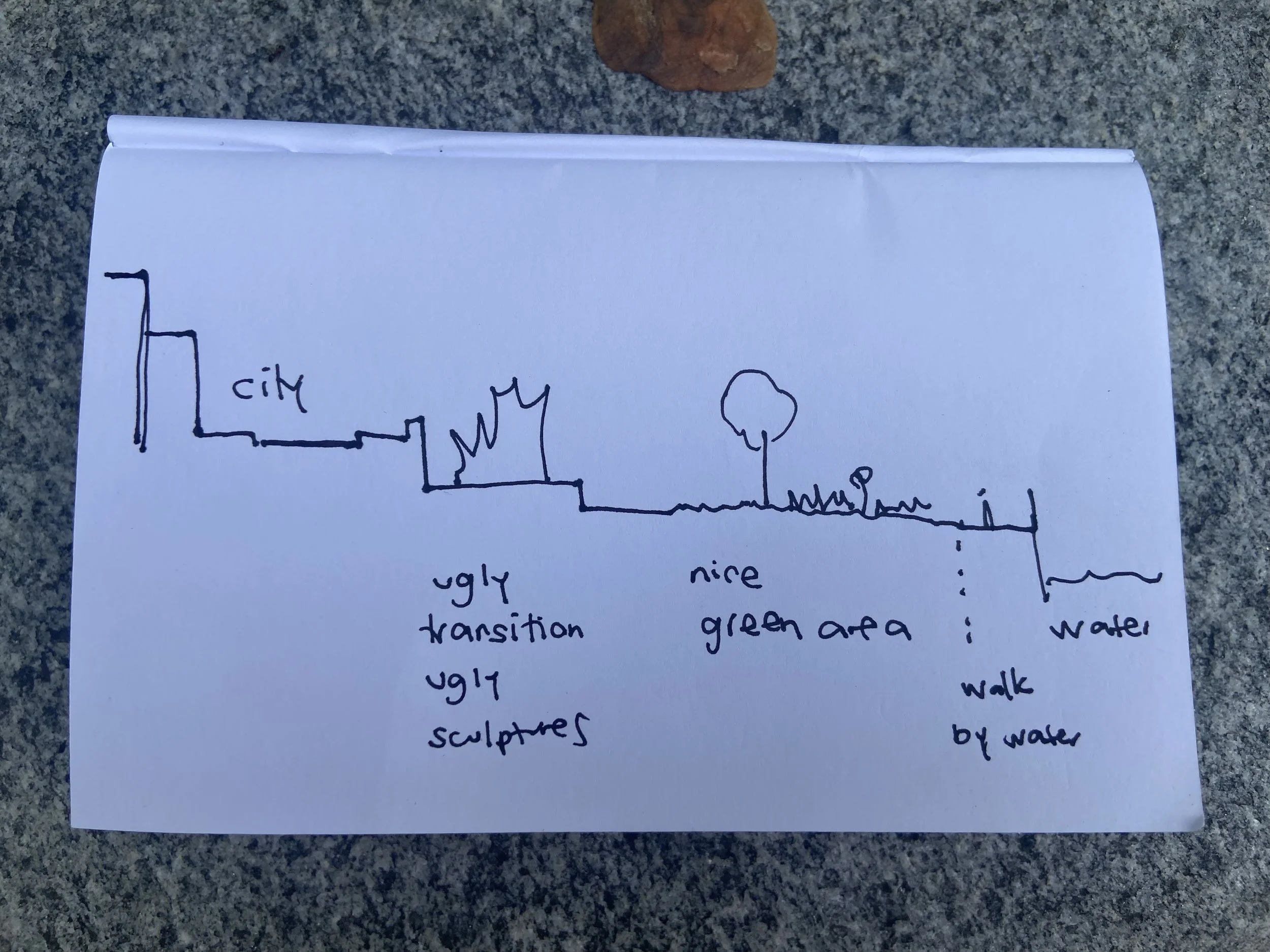

A drawing submitted to our survey while conducting our first pilot at Rockefeller Park with the Design Trust. Source: Survey Submissions

Both design partners wished to gather feedback from neurodivergent people synchronously and asynchronously. While synchronous methods enable richer follow-up conversations, asynchronous surveys could boost participation and support longitudinal data collection. The design partners were also interested in the possibility of having unguided evaluations to reduce researcher bias. They were particularly enthusiastic about receiving multimodal feedback, such as photos, video, and audio, which are potentially more accessible for neurodivergent participants. While the partners had different preferences regarding group vs. individual evaluations, both approaches offer unique benefits. Ultimately, we concluded that the digital feedback tool should be usable across a variety of research contexts.

Next, we reached out to neurodivergent people on the Design Trust’s Advisory Committee to learn more about their experiences and preferences regarding public spaces. They highlighted challenges with both sensory understimulation and overstimulation. They also emphasized the value of having more information about how other neurodivergent people experience a space, as this can help them assess the space’s accessibility before visiting. Above all, we learned that making public spaces accessible goes beyond making the place itself accessible. As mentioned during the interviews, neurodivergent people may require more time to “wind up” or prepare to go outside. Thus, designers must first consider how to support and encourage neurodivergent people to go to and engage with public spaces, rather than stay indoors.

The Survey

A screenshot of our survey, designed to crowdsource data about the accessibility of public spaces for neurodivergent people.

Based on our insights, we determined that a survey to crowdsource urban accessibility data could provide neurodivergent people with the necessary information to determine whether a public space would be accessible to them. The results of such a survey could also guide decision-makers — such as researchers, designers, and policymakers — by offering valuable insight into current access issues and suggesting ideas for making surveyed public spaces more accessible and enjoyable to the neurodivergent community.

I researched a variety of technologies (e.g., survey tools, customizable maps, digital whiteboards, social media platforms, and mobile device measurement tools) that we could use to help us collect this data. Based on insights from the earlier audits and interviews with neurodivergent self-advocates, we prioritized platforms that support multimodal data entry, such as photos, videos, and audio files. Although we considered developing a new system for conducting public space accessibility assessments, we ultimately chose Google Forms as the survey platform due to its familiarity, ease of use, and flexibility. In terms of the data to collect, we included questions about decibel levels, ambient temperature, weather conditions, and the amount of available shade. Open-ended questions, including probes about the sights, sounds, and smells of a space, allowed respondents to elaborate on specific aspects of their experience.

We tested our survey prototype both internally at the Design Trust and with attendees at a Public Space Potluck held at the Socrates Sculpture Park in Astoria. These two pilot studies provided us with valuable insights that helped us refine our survey design, enhancing its clarity and focus.

Socrates Sculpture Park, the site of the Design Trust's August 2024 Public Space Potluck. We conducted a small-scale pilot of our survey at this potluck! Source: Lucy Jiang

The Impact and Path Forward

Through this project, the Design Trust for Public Space does not aim to create a one-size-fits-all approach for designing public spaces that are accessible to neurodivergent people, given the diversity of public spaces and the range of personal preferences. Instead, my hosts and I aim to design and develop crowdsourced solutions that provide neurodivergent people with more information about what a space might be like, allowing them to make informed decisions about how and where they wish to engage in public spaces.

Looking ahead, we aim to finalize and distribute our survey and share our findings with key decision-makers, such as designers, researchers, and policymakers. Our goal is for our insights to inform future efforts to improve neurodivergent accessibility in public and urban spaces in general.

I am incredibly grateful for the opportunity to work with the Design Trust through the Siegel PiTech PhD Impact Fellowship. It has been a great experience to translate academic research into practice and policy, and I am excited to have continued working with the Design Trust on broadening the impact of this project in fall 2024.